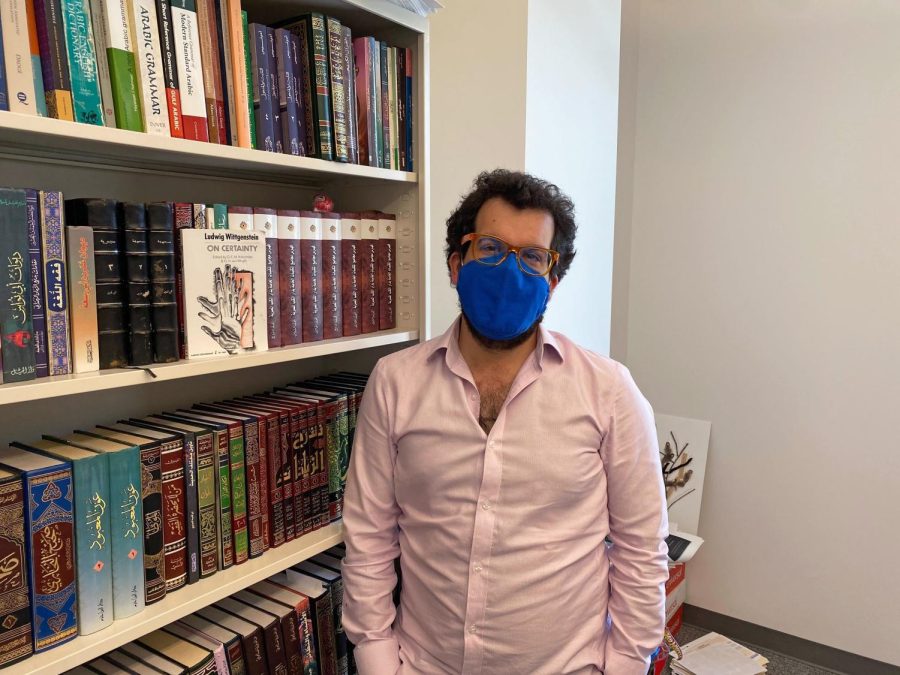

Office Hours: Elias Saba, Religious Studies, History, SAMESA

Elias Saba, a self pronounced non self-hater.

April 24, 2023

In Office Hours, Raffay Piracha `25 sits down with faculty to learn how their scholarship provides them with equipment for living.

Grinnell is full of haters. And by that, I mean a bunch of people who seem to hate themselves. Really, you can’t walk fifty feet without overhearing someone here talk about what a “terrible person” they are for not balancing their school and work life, or falling behind in a class, or forgetting their dog’s birthday, or forgetting to apply for a summer internship or waiting to pick up four packages at one time from the mailroom.

Look, I don’t want to undermine the severity of any mental health crises, but if there is one thing my history classes have taught me, it’s that humans have always felt like shit, have always self-loathed and are always in crisis, and it really isn’t their fault. We’re no exception! So, yes, let’s acknowledge that capitalism is wreaking hell on our work lives, and that the cost of attending college (and this school in particular) is way too much. Yet, despite all of our super cool and hip faculty reading bell hooks and preaching Marx, the workload here doesn’t seem to respond to the reality of our financial burdens as students and workers.

This installment of Office Hours isn’t meant to cudgel you into submitting to your lack of agency over your life. Instead, this is about methodically surviving the pressure of inflexible demands and making sure you don’t internalize the academic myths that shame you for not having the time you need to feel good about your work ethic. You are not worthless for not mastering all twelve or sixteen or eight of your credit hours. And sometimes you just need some guy with a Ph.D. to tell you not to hate yourself. Since I vaguely mentioned something about history and school and hatred, I asked two-time Ivy League superstar, self-proclaimed hater (although crucially, not a self-hater) and scholar of premodern Islam, Assistant Professor Elias Saba, religious studies and history, and chair of studies in Africa, Middle East, and South Asia about time management.

***

Elias Saba, how much time should one devote to preparing for class?

That’s a good question. You know, we’ve talked a lot about that as faculty. I was always under the assumption that for a four-credit class, you would do one hour in class and three hours outside of class. And I assumed that that’s literally where three of the four credits come from, if you know what I mean.

Yeah, it’s interesting given the emphasis on subjectivity in the humanities, and obviously because the amount of time everyone spends on something is going to yield different results. People often speak about workloads as if they’re comparable. Like someone can spend four hours reading twenty pages. Someone can spend two hours on one hundred pages, etc.

Yeah, and part of that is also like, what do you consider for work to be “done?”

I guess that’s the question. Like, when do you tell a student to just “throw it?”

I would never tell a student to throw it in, and I don’t think that’s a productive way of thinking about things. I think if you’ve gotten to that point then you haven’t thought about what you’re doing in the ideal way. Because I think instead of thinking about, like, throwing it, you should think about the tasks you have to do in terms of their importance. So, for class, if you are working on a paper, what percent of the grade is it? And then that’s on one level, and then on another level, like, how important is it to me personally? And so, if it’s something that’s both very important to you and worth a lot, you should devote a lot to it. But if it’s not, then good enough is “done.”

How do you resolve the contradiction between wanting to complete the work and practical considerations like, say, working on and off campus to make ends meet?

I think part of that is thinking about what it means for work to be done. I think students don’t talk about it amongst themselves very much, but I think they have very different ideas of what the phrase, “I finished all my reading” means. And similarly, like, “oh, this paper is finished.” And so I think in some kind of extreme situation, with a student who works a lot of hours, who maxes out their time on campus, and who works, you know, an ungodly amount of hours off campus — they might still be able to do all of their tasks if “doing all the tasks” means do them to the minimum amount necessary to move forward. And sometimes if that’s all you can do, there’s nothing wrong with that. I think that we in academia, but particularly at Grinnell, really try to emphasize that things should be done as good as we can, and I don’t think that’s a smart way of thinking about things.

Okay, you have a family, teach several courses, how do you respond to the necessary conflicts that arise from these commitments?

Yeah, sometimes things just aren’t that good. There’s not a conflict there. Sometimes life turns out a way where I don’t prepare for class that well, and then class isn’t that good. Sometimes it works out differently, where I have to do a research thing, but I don’t have enough time to devote to it, and so that’s lackluster. Sometimes I can’t give my kids the time they need. I don’t find a conflict there. That’s just like the tradeoff of life.

So, you’re telling me you don’t hate yourself?

No. That’s part of the importance of setting up expectations: “how much care should I put into this?” Part of that is not that you’ll care very little with a great result at the end. You’ll care little, you’ll get a result that reflects that. Not necessarily in a negative way, but then it’s like, “oh, that’s good. It wasn’t worth very much. I didn’t put that much time into it. And I got to move forward.”

So, why don’t faculty tell us all of this from the onset?

Because I think that in some way we’re all competing, right? I want all your time. Not all of it, but I want your time and attention. I want you to care about the class the way that I do. But there’s nothing wrong with you not caring in the same way. I think for me part of what I hope to get across is how much I love the stuff that I teach. And I think talking about how you shouldn’t do the work, or that it’s not that interesting undercuts the thing that I’m trying to sell.

Yes, but it isn’t necessarily a question of whether a student wants to do the work, it’s a matter of whether they can. Why don’t syllabi make it feel safe to sometimes forgo preparation?

I’ve always approached things by thinking about, “what benefit will I get if I do that?” and “what consequences will I have if I don’t do that?” And if you are happy to accept the consequences, then you should be happy to not do anything. So, on my syllabus I have a policy that you have to do every assignment to pass the class. And one reason why I have it in there is because I know that if I were a student and that wasn’t in there, there’d be nothing [from me]. It might be a good idea to do enough work so that I have achieved a C, take the class pass/fail and then stop, because it’s done. I think the other thing is there’s like a real magic in assigning yourself X amount of time to do a task and then stopping when the time stops. And so, you have a reading and give yourself an hour to do it. And then after an hour, you only make it two thirds of the way through. That’s it. It’s okay. You did it.

To bring it home, the question is, what would medieval Islamic legal scholars say about managing time?

They seem to have had endless time in a way that I don’t quite understand. They certainly seemed to have thought that sleep wasn’t very important. Really, that five-ish hours of sleep per night is good. I try to get seven or eight. But they seem to have had jobs that let them focus on nothing but the production of new texts.