Remembering President George Drake `56

George Drake `56 leaves behind a loving family and an inspiring legacy.

November 21, 2022

When the granddaughters of George Albert Drake `56, Elizabeth Drake and Hannah Drake `18, were cleaning up his home office, they came across books and documents revealing his many accomplishments.

“Oh, I didn’t know that,” said Hannah, who was unaware of the breadth of Drake’s legacy.

If you had a conversation with Drake, he was often more interested in you than anything else — his humility and affection overpowered his long list of accolades.

“He really made you feel like you were the only person in the room,” Hannah said.

After a long career in Grinnell, where he went from a student, to a trustee, to a professor, to president to a professor again, George Drake, 88, died on Saturday, Oct. 15, 2022 in the Mayflower Home surrounded by his family.

He is survived by his wife Sue Ratcliff Drake `58; their children Christopher, Cindy and Melanie Drake `92; and six grandchildren Nicholas, Elizabeth, Hannah, Danielle, Lila and Samantha (Sam) Drake-Flam `25.

A friend and colleague of Drake’s, President Anne Harris said Drake had “an enduring fascination” with the College. During his time as a student, he led his cross country team to its first conference championship and won the Archibald Prize, awarded to the person with the highest grade-point average in the graduating class. In 1970, he became a trustee, and in 1979, he went on to be the first alumnus to serve as president.

Stepping down in 1991 after 12 years in office, he and his wife Sue dedicated themselves to the Peace Corps, advancing education in Lesotho. In 1993, Drake returned to Grinnell where he taught history for a decade. He retired at 70 but continued to teach a tutorial class at the College and with Grinnell’s Liberal Arts in Prison Program at Newton Correctional Facility. He has lived in the town of Grinnell since.

“He knows every corner and every stone,” said Harris.

From their conversations, Harris, who noted “the twinkle in his eye,” found that Drake was interested in how the College governs itself. According to Harris, Drake often wondered, “What will our students teach us next?”

Harris and Drake often ate and chatted together at Michael’s, a restaurant that closed over the pandemic. Drake ate champagne cake and thought it was the best cake in Grinnell.

When Drake led the campus tour at a new faculty orientation, he laughed as they passed by the Burling Library. “I’m the one responsible for the monstrosity on the top of the library,” Harris remembered him saying, referring to the boxy third and fourth floor addition that Drake approved.

When Professor of History Sarah Purcell `92 was a student, Drake served as president.

She remembered his presence as whimsical. He would ride his bike around campus, casually go to football games and wave at the people playing naked frisbee.

“No big deal. He wasn’t really fussed by any of it. He just had a sense of humor about the world and didn’t take anything too seriously,” Purcell said.

In her first year, students tried to pull a prank by inviting first-year students to have pizza at the president’s house. Once people started showing up, Drake and his wife didn’t want to send the students away, so they scrambled together some ice cream for an ice cream social, which persisted as a New Student Orientation staple during his presidency.

Later, when they became colleagues, Purcell learned that Drake was also president of his high school. He successfully led a campaign to win a contest in which the senior class needed to sell the most greeting cards in the country, which would allow Duke Ellington to perform at the senior prom — an early sign of Drake’s effective leadership.

During the fall of 2019, Drake taught a tutorial class about leaders in history called “Crisis, Liberation, Justice and Leadership.”

Sometimes, the class would meet for breakfast at the beginning of class in the Whale Room in the dining hall. Here, they would transition from casual conversation to heated debates relating to the leaders they learned about.

Drake would also invite his students to his house to watch long movies on the leaders they studied. He and Sue would prepare popcorn and brownies.

“It was the classic grandpa’s basement type thing,” said one of his tutorial students Jacob Cowan `23.

At one of the movie events, Writam Pal `23 ate more than eight brownies. George took note of this and handed a recipe card to Sue for her to fill out. Pal still has Sue’s recipe in his home in India.

Pal also said that Drake had given him a “reality check.” When Pal would miss classes, he made up many excuses. Drake told him something along the lines of, “You need to pull your pants up.”

“He was the first professor who actually was very patient with me because many professors gave up,” Pal said.

As an international student from Ecuador, another one of his tutorial students Antonella Diaz `23 said, “He helped me so much to find strength in my own voice and to feel confident that I am meant to be here. That I earned my spot to be here, that I can be in a level playing field with people who are here.”

As she sought to strengthen her ties to spirituality at Grinnell in her first year, Drake invited Diaz to join the choir in Herrick Chapel. As they would sing alongside one another, Drake would keep Diaz, who was unfamiliar with how to read sheet music, on track by pointing out where they were in the music.

Diaz said, “I don’t know if I necessarily have a lot of memories that come up, but a lot of feelings do.”

She once went to his office crying and came out laughing. “How did I even laugh? I thought I was going to spend my whole day in my bed crying.”

He would continue to extend a hand to his students by welcoming their visits and phone calls after he stopped being their advisor. During the start of the pandemic, Cowan was feeling lost about which direction he wanted to take. Drake reminded Cowan to “not default to academics.”

Because granddaughters Hannah and Sam studied at the College, they were able to visit their grandparents more readily. Sam would come over to their home and show them her art.

“He would be like, ‘show your grandmother,’ and have this enthusiasm and light in his eyes,” said Sam.

When Drake worked with influential societal figures, he would tell them about his children and grandchildren. “All these important people, and yet he was so proud of me,” said Hannah.

When Sam committed to the College, she first broke the news to her grandparents over the phone before she told her parents. At Hannah’s graduation, it was her grandfather who handed her her diploma.

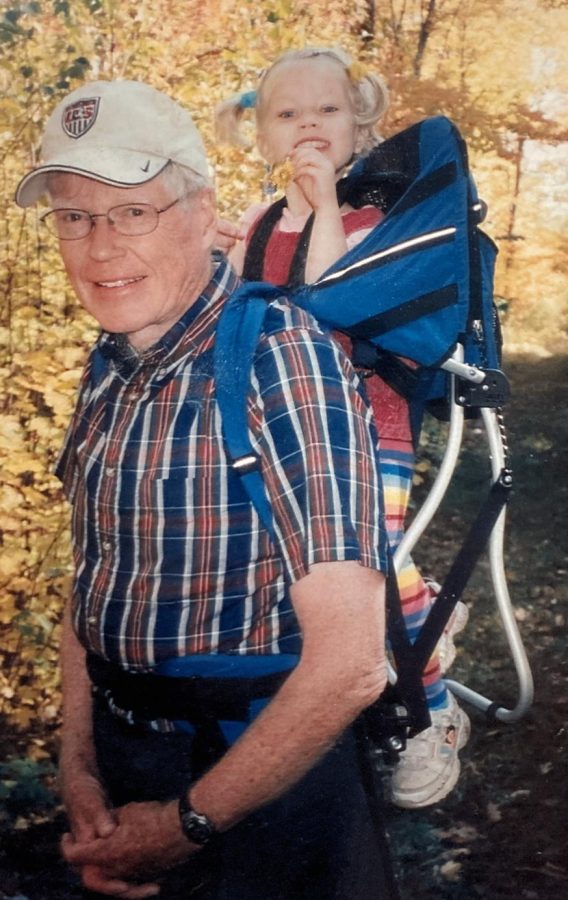

When she was a child, his daughter Melanie would run with him near their home in Colorado. Hannah is fond of family hikes in Colorado near the cabin that her grandfather built himself. The Drake family loved adventuring together.

Up until three weeks before his death, Drake could be seen around campus riding a recumbent bike, even in the winter. While his pancreatic cancer worsened, he got a hold of this particular bike once his regular one proved too difficult to ride.

Two days before he passed away, the doctor had told him that he would need a wheelchair. Drake refused.

As he was passing, Hannah posted a notice on a Grinnell alumni Instagram page that called for those he impacted to send their notes to him. He received over 50 letters. As his family read them aloud to him, they noticed a trend of people thanking him for the compassion he showed them and how he encouraged them to follow their passions.

In a reading for Sam’s GWSS class, the phrase “living legend of an institution” stuck with her — what she believes to represent the essence of her grandfather.

On Saturday, Nov. 19, the family hosted George Drake’s “Celebration of Life” service in Herrick Chapel, where his family and those impacted by him gathered in honor of his expansive legacy.