History Takeover: The winding path of coeducation at Grinnell

Contributed by the Grinnell College Library Archives

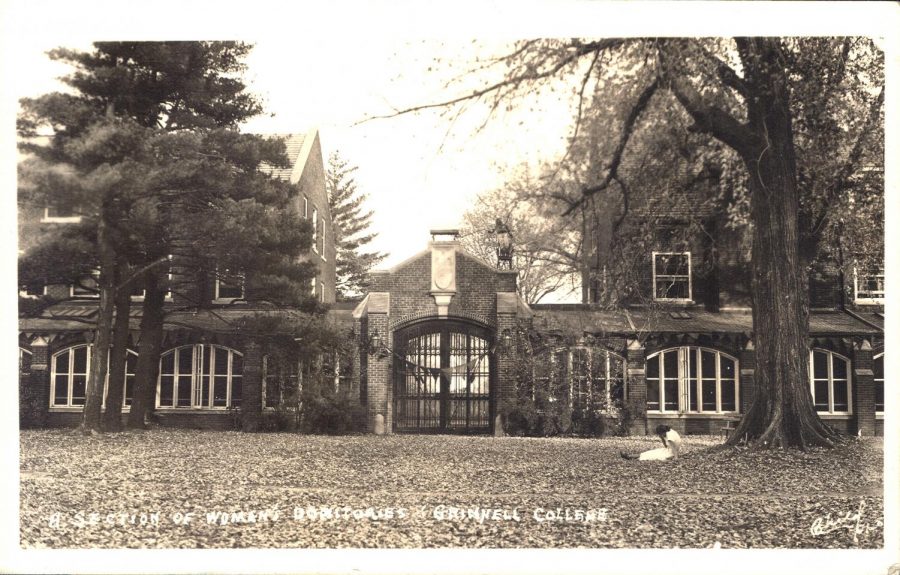

In this photo, all women students at Grinnell lived in South Campus residence halls prior to dorm integration in 1968.

March 6, 2023

There is a short and optimistic version of the story of coeducation at Grinnell College– — the school began accepting women in the 1860s and expanded extracurricular opportunities for women a century later, so that by today, it has become truly coeducational.

That story is not necessarily wrong. Yet, it obscures the nuance of coeducation at Grinnell by reframing it as a natural, inevitable outcome. In fact, the process has sputtered along in leaps as well as with backslides, responding to particular incentives at particular times.

Grinnell has admitted women since the Civil War, according to Joseph Frazier Wall in “Grinnell College in the Nineteenth Century.” Most young men were drafted to fight in the war, so the school allowed women to enroll in order to boost enrollment numbers.

In 1865, Joanna Harris Haines became the first woman to graduate from Grinnell College. However, the College perceived “ladies’ education” as inferior, and despite earning a diploma, Haines did not receive a Bachelor of Arts, or any degree, for her efforts.

Over the next half century, female enrollment developed unevenly. According to Professor Martha Foote Crow — one of the first women in the country to receive a doctoral degree and a vigorous proponent of coeducation at Grinnell in the 1880s — an average of five women graduated Grinnell each year for the two decades following the 1860s. After, the pace accelerated so that women accounted for roughly half of the graduating class by 1920, according to Tamara Beauboeuf, professor of gender, women’s and sexuality studies.

While women gained full access to academic offerings during this period, residential life remained segregated. Men lived in north-campus dorms, while women resided in south-campus ones. Both halves had separate student governments, recreational facilities and extracurricular activities.

The College worked hard to maintain the division. In the paper “The Transition to Coed Residential Life at Grinnell College,” Eli Zigas `06 explains that the school locked the south-campus loggia every night so that men and women could not interact unsupervised.

The College also had separate versions of student affairs, headed by the dean of men and the dean of women. Beauboeuf emphasized how the deans of women represented female voices on campus.

Referred to as “architects of belonging” by Beauboeuf, these administrators guided women through a male-dominated space by speaking on their behalf, pressuring the administration and implementing extracurricular events.

In the 1960s and 1970s, second-wave feminism engendered coeducational reforms at hundreds of college campuses including Grinnell. For instance, as Title IX became law, women gained access to athletics.

Likewise, the longstanding policy of residential separation ended. Zigas finds that there were no coed dorms in 1967, but by 1974, only Dibble Hall and Smith Hall were single-sex dormitories. And with the change in location, the student government became the Student Government Association (SGA) known today, with equal chances for representation for students of all genders.

However, Scarlet & Black papers from this time period introduce another layer of complexity to the narrative. By and large, students did not premise their support of dorm integration on gender equality — they instead protested rules against opposite sex visitations at night.

Students essentially argued that residential separation rules stopped them from having sex. After years of op-eds and student government resolutions, the College relented in 1968.

Even then, the story was not complete, as Beauboeuf explained, “Making [Grinnell] one campus means that it became a men’s campus again.” The loss of a space specifically for women, and thus the loss of the dean of women, carried negative consequences.

In 1972, the SGA eliminated a position reserved for women, turning it into the vice presidency. This decision received little attention, meriting seven short sentences in the SGA meeting minutes.

Coeducation is an ongoing challenge. The uneven dropout rates in STEM fields prove that women continue to face challenges in accessing higher education, including at Grinnell. When understood through the lens of intersectionality, the picture dilutes further: Edith Renfrow Smith `37, the first Black woman to graduate Grinnell, did so 72 years after the first white woman. The more one looks into coeducation, the less short, optimistic and simple the story turns out to be.