ChatGPT’s potential to rewrite the classroom

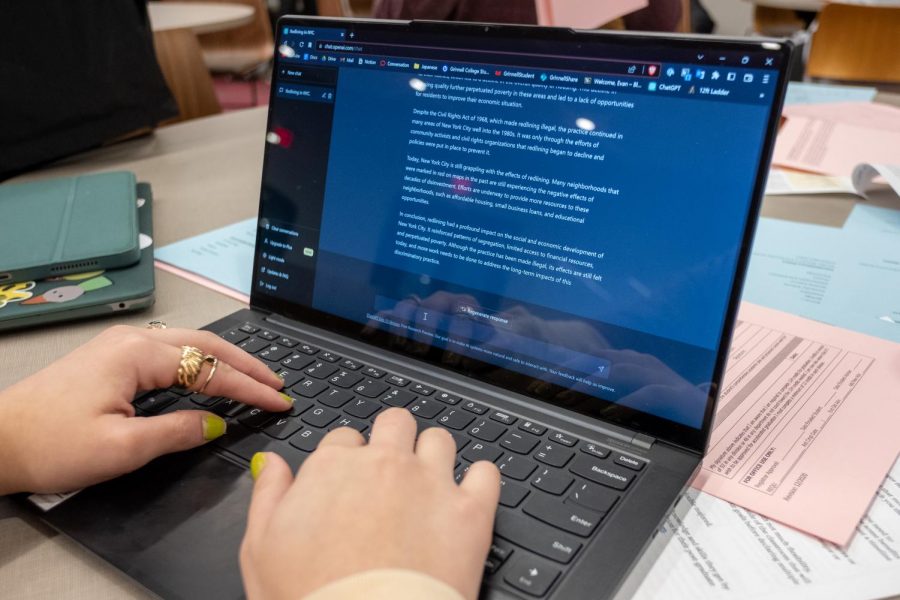

Photograph illustrating a student using ChatGPT, an AI program which generates text.

February 27, 2023

Since ChatGPT’s public launch on Nov. 30, colleges and universities across the U.S. have reckoned with the widespread use of the chat bot, capable of writing complex texts powered by artificial intelligence (AI). Already, the New York Times has reported that a Northern Michigan University professor caught a student submitting a religious studies essay written by ChatGPT just weeks after the software’s release. Further, a January survey with nearly 5,000 Stanford University respondents showed that 17% had used ChatGPT in submitting written work during the university’s prior term.

At Grinnell College, the public accessibility to ChatGPT and reports of ChatGPT usage by students has created questions amongst members of the College’s Committee on Academic Standing (CAS) on how to appropriately regulate, address and respond to the rise of assistive technology. For some faculty at the College, the availability of ChatGPT has already begun to affect classroom pedagogy.

Karla Erickson, professor of sociology, said she incorporated a staggered revision process to her courses, where students are required to submit early drafts of papers and explain further changes to their work.

Erickson said she met with a group of eight alumni, three of whom already used ChatGPT in their jobs, to gauge if and how professionals were using ChatGPT in their work. Later, Erickson had students in class review a discussion involving a response to ChatGPT’s generative text. One student, Erickson said, described generative text as CliffNotes but on hyperdrive.

“You need to treat it like a tool and know what its limits are,” Erickson said. “In order to do that, we have to make it an object of our analysis. What is this thing, really? And what is it good at?”

Erickson said she has seen individual faculty at other colleges and universities institute more drastic changes to coursework or exam structures in response to ChatGPT, such as switching written papers to oral examinations. But Erickson said it’s essential that faculty refrain from instituting drastic changes to courses in response to an emerging, complex and misread technology like ChatGPT.

“Don’t overpivot. We don’t have to throw out everything we do,” she said. “If we get confused about the line between this and science fiction, it ascribes a significance to it that doesn’t yet exist.”

For Erickson, she sees possible violations of the College’s academic honesty policies from ChatGPT with a similar eye as previous violations. Violations of the guidelines arise when students believe they no longer have the time or energy to complete course work in line with standard academic conduct, she said.

“It doesn’t come out as an intent to get away with something,” Erickson said. “This becomes a very tantalizing tool at 2 a.m. in the morning.”

As AI advances, the College’s academic honesty policies may require some adjustments, said Christopher French, professor of mathematics and statistics and chair of the CAS subcommittee on academic honesty.

While French said the majority of the policy may not change, some language in the guidelines calls for adjustments, such as short phrases like “someone else’s idea” or “someone else’s work.” While innocuous before ChatGPT, this wording may imply that plagiarism or academic misconduct arises exclusively from ideas generated by a human being, rather than by an artificial intelligence chat system, he said.

Discussions about ChatGPT amongst CAS members are only at the beginning stages, said Cynthia Hansen, associate dean of the College. The next CAS meeting on ChatGPT has yet to be scheduled.

“The use of generated material that doesn’t come from your own head is something that would already be covered in the scope of our policies,” Hansen said. “We have a college-wide expectation to cite sources that are not your own, and so in some ways, the policy already covers these types of artificial sources.”

This specific change to the academic honesty policy could take around a year to implement, according to French. Yet Erickson said that the race to produce more intelligent, more sophisticated AI is likely to proceed faster than the College can respond to the technology, especially as large companies like Microsoft invest billions of dollars in OpenAI, the organization responsible for ChatGPT.

“It would be hard for any school, even a school like Harvard, to keep up with that,” Erickson said. “There’s a kind of agility here that might be required.”

But Erickson said she does not think ChatGPT will collapse the traditional standards of academia. Some work produced by ChatGPT will go unnoticed by faculty, but some conventional violations of academic honesty have always flown underneath the radar, French and Erickson said.

“There are other ways that students have done things in the past. This just seems to make it a lot easier and create temptation,” French said. “It’s hard to detect. So yeah, that concerns me.”