As anyone who has ever looked at the College music department faculty page knows, the College provides a dizzying variety of private lessons, special-interest ensembles and performance groups.

With a 40-member faculty, the music department is unusually large. This is mostly due to the presence of Applied Music Associates, or AMAs, who teach private lessons in disciplines that vary from the bagpipe to the cello.

Fred Buck is an applied music associate at the College, and teaches private lessons in banjo, mandolin and resophonic guitar, an instrument found mainly in bluegrass music.

Buck has been teaching at Grinnell for over 25 years, with his student numbers growing from just two in his first years at the College to over twenty this semester.

Buck, who has been playing the banjo for over 40 years, teaches in Music House (1032 East St.) every day of the school week from around 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Buck also organizes “jams” where students have the chance to play together.

“My whole goal is to give them a lifetime’s worth of playing … it’s not just to learn an instrument; it’s to fit in with other people and play,” he said.

“I call music a participant sport. [Playing in a group] is more than just playing an instrument … and I think the only way you can learn that is to play with people.”

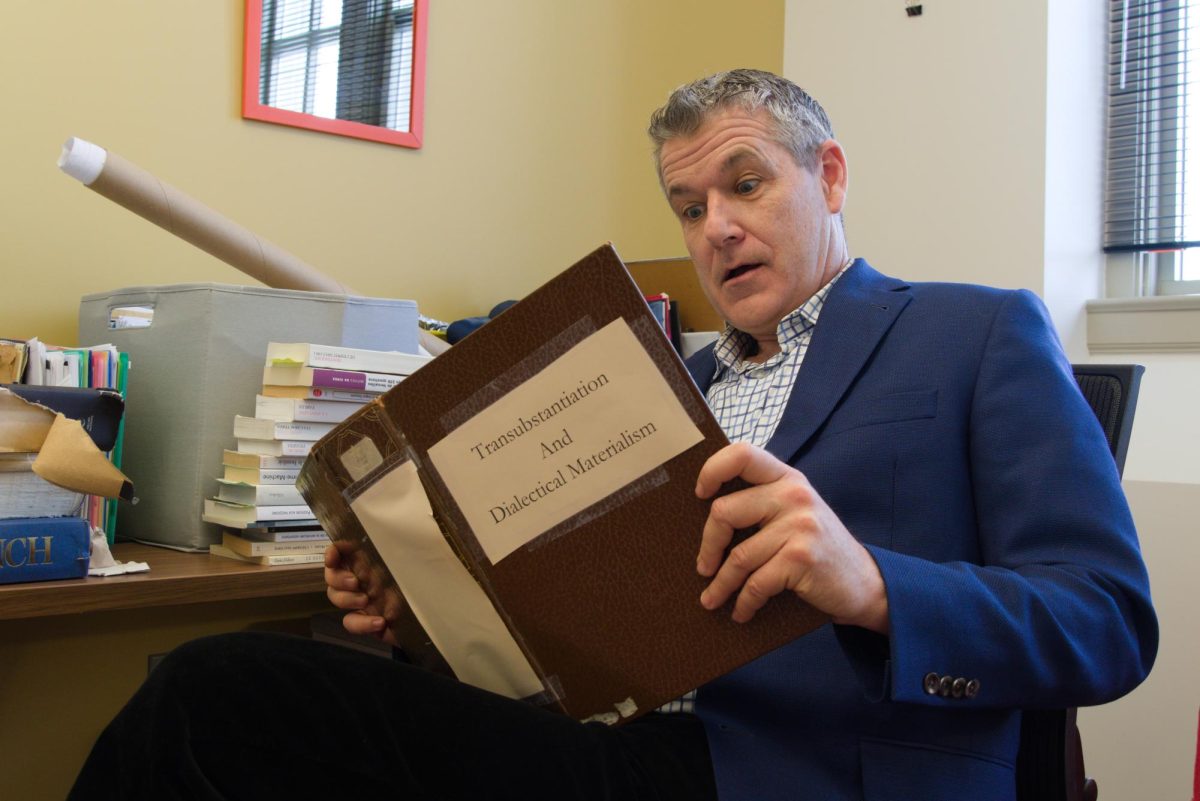

Professor Eric McIntyre, chair of the music department and conductor of the College orchestra (in addition to many other musical pursuits), explained that the majority of AMAs teach exclusively in a one-on-one setting, and that most of them do not live in Grinnell, but commute from one of the nearby cities. Almost all AMAs at the College work as professional musicians simultaneously with their teaching position.

“Essentially, that’s the one requirement, that someone be a working musician,” said McIntyre.

AMA positions are not tenure-track, but rather have contracts that are renewed on a year-to-year basis. McIntyre explained that due to this fact (as well as that AMAs tend to have at least one other job outside the College), the music department has a much higher rate of faculty turnover than most other academic departments at the College, where all or almost all positions are tenure-track.

“They have faculty status, at least in that they have faculty p-cards and … library benefits,” McIntyre said. “Some have beenfits and the benefits have to do with if they are over a certain number of hours … most, or many, its just an hourly contract, so they’re paid based on how many students they teach.”

Hiring for the positions is partially determined by the specific subjects students want to study. For example, if a particular instrument is very popular and there is a shortage of faculty to meet the demand for lessons, the department may decide to add another AMA who specializes in that instrument.

Regarding the more unusual instruments, McIntyre explained, “Rarely do we say [that] we want to just offer an instrument and go and find the teacher — there’s usually some question of demand, and then of course there’s all the standard orchestral instruments and band instruments and voice, which we want to always have staffed.”

For some rare specialties, it has been difficult for the department to find available teachers.

A specialist in the cornetto, an early music predecessor of the trumpet, teaches over Skype due to the difficulty of finding a local cornetto virtuoso.

On the other hand, McIntyre said, there have been occasions in which, by chance, a specialist was available within the local community.

“When we added bagpipes, … we just happened to have a virtuoso bagpiper here in our community who could teach, and along with that, there was some curiosity from students, and so in that case we were able to add that,” McIntyre said.

When students wanted to learn the accordion, the department found an instructor even closer to home.

“It just so happens that Joyce Bergan, who works in our office, is an accordionist” McIntyre remembered, “and so she was able to start teaching that way.”