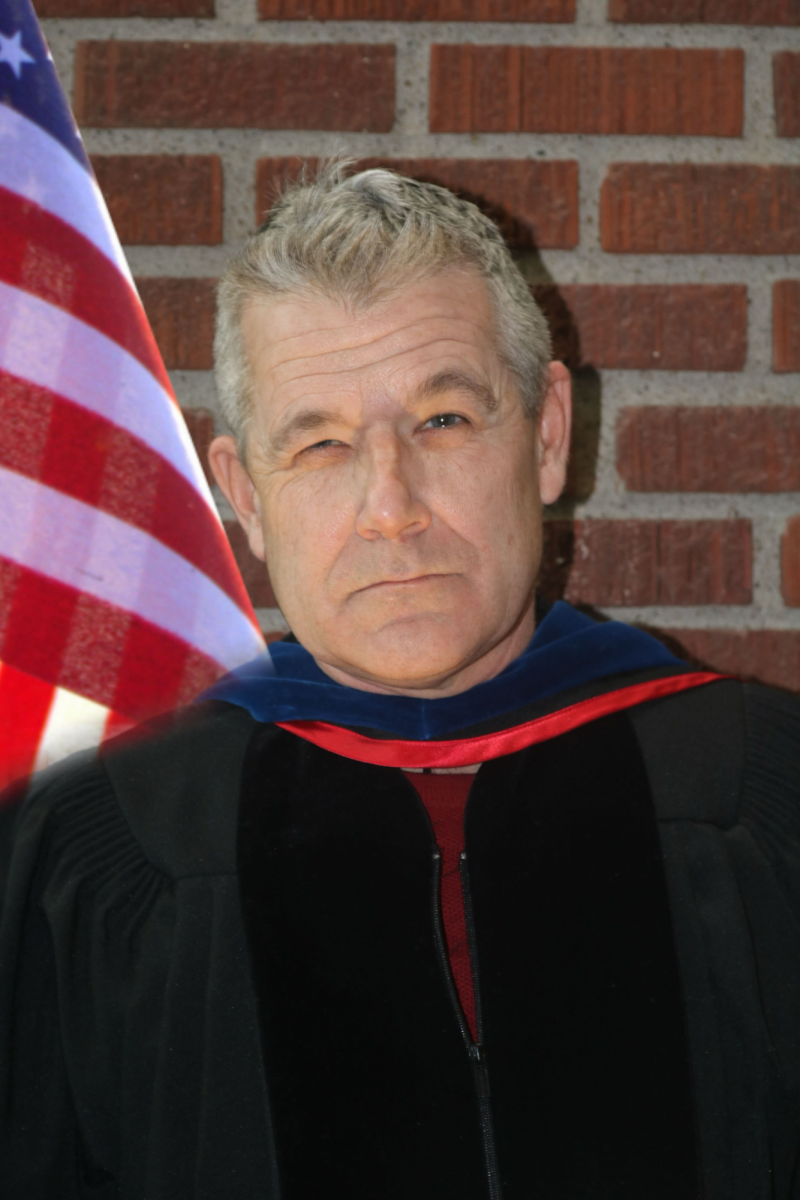

During last Tuesday’s seminar and roundtable discussion “The Wealth of the Black Snake,” Sebastian Braun, the director of the American Indian studies program at Iowa State University, spoke about the effects of the Dakota Access Pipeline on both Native and non-Native communities and the controversies surrounding the construction of the pipeline. The talk was sponsored by the Center for Prairie Studies.

Despite being born in Switzerland, Braun became interested in Native American studies from an early age. He recounted reading books on American Indians at an early age, and became immersed in their different cultures. After receiving his degree in Ethnology, History, and Philosophy from Universitaet Basel, Braun traveled to the United States for his Master’s in Anthropology and Folklore and a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Indiana University.

Now an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Iowa State University, he works to educate the non-Native population of the United States about Native culture and how it is marginalized by both the government and the public.

The roundtable discussion was informal in nature and allowed for the audience to directly ask Professor Braum questions about his field of work and interest. As can be imagined, many of these questions related to the controversy over the construction and location of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL).

The pipeline, which was completed in 2017, passes 500 feet from the edge of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in an unseeded territory. Braum described it as “limbo because the [United States] government paid the tribe over 200 years ago for the rights to the land” but “the tribe never accepted the money.”

This would mean that legally the land is owned by the federal government because it was purchased, even though the money has yet to be collected. Unfortunately, this also means that should the reservation have sued to prevent the construction of the DAPL, the Supreme Court would have found the pipeline’s existence to be legal under eminent domain — the federal government taking private property for public use — because payment was given in exchange for the land.

The initial discussion over the construction of the DAPL led to an even more interesting talk about the treatment of Native Americans in the United States. Braun mentioned a Supreme Court case from 1831 in which Native American tribes were established as “domestic, dependent, sovereign entities,” a phrase that has yet to be deciphered to this day.

“As dependents of the federal government, the people living within a reservation have no real say over their status as a legitimate tribe, and, as a sovereign body, any court case filed had the potential to go to the Supreme Court where it will be found to be constitutional because the reservations are under the care of the United States,” Braun said.

A final topic discussed during the roundtable was the expectations of Native Americans in the modern United States. Despite “American culture being expected to grow and change,” Braun said, “American Indians are supposed to remain the way they were in the 1800s to be considered Native.” This is due in part to public opinion of Native culture which widely revolves around stereotypes of past centuries. Braun stated that “until the American Indian culture is accepted by the majority of non-Natives, we can expect even more pipelines to be built on their land.”

The complex nature of the discussions and its free layout piqued the interest of many of the audience members. One guest, Mica Lin-Alves ’22, said that the roundtable taught him about “the contradictions in the rights given to indigenous people by the Supreme Court” as well as “how their rights and oppression is based on stereotypes and how they are perceived as being Native.”

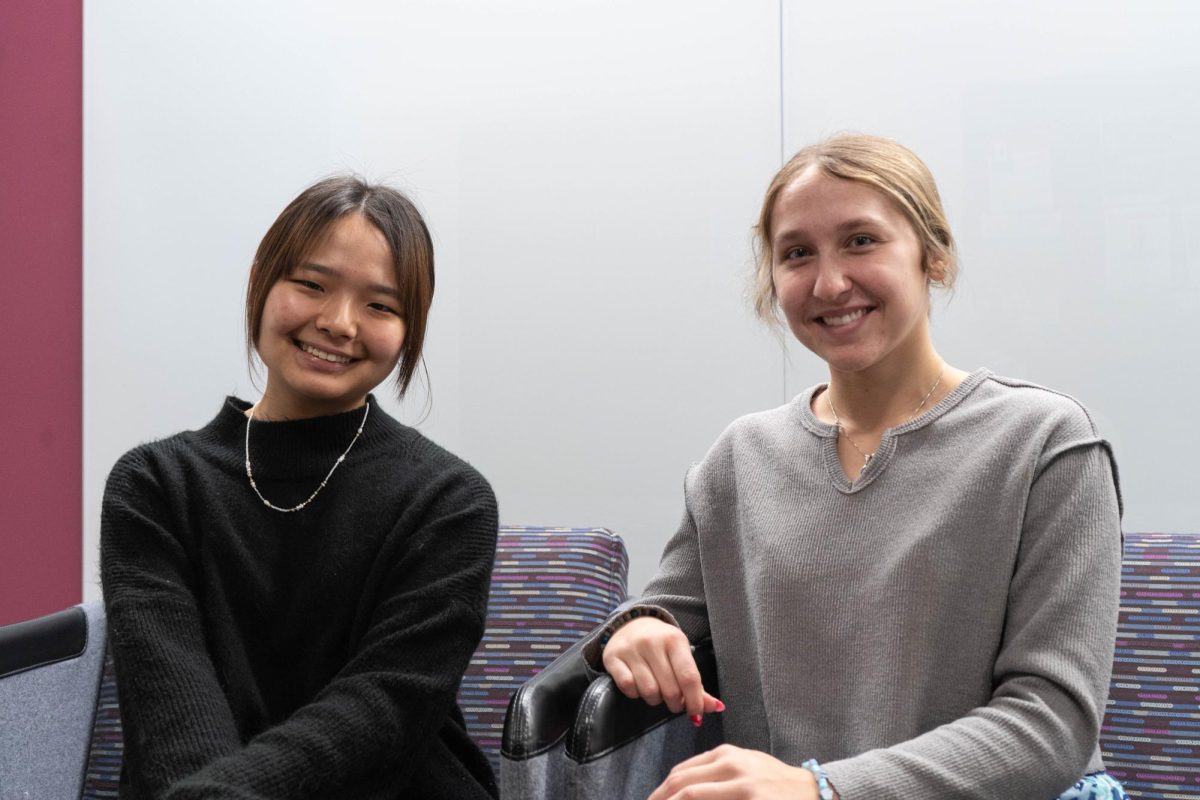

Photo by Sarina Lincoln