As Iowans celebrated Labor Day this Monday with parades and picnics, labor unions — a now controversial subject in the halls of Congress and the Statehouse — were featured prominently in the speeches and celebrations.

Denny Conway, a retired Grinnell-Newburg School District teacher of 44 years, spent his life around labor unions. In 1973, Conway accepted a teaching job in Grinnell and joined the National Education Association, which negotiates on behalf of teachers.

Conway was born in Nebraska, into a family of railroad workers. While Conway avoided joining the railway union, the rest of his family enjoyed the union’s benefits. And without the union’s protection, Conway believes the railroad management “would have ran right over [the workers]. I think they would have pushed and shoved … and you would have had unsafe conditions.”

John McKerley, an oral historian for Iowa Labor History, traced the history of Iowa unions. According to McKerley, Iowa unions started in the late 1800s, when they arose to combat economic uncertainty. In the Great Depression the U.S. granted private-sector workers the legal right to unionize. McKerley ended today, when Iowa unions are weaker than ever.

Iowa is a low-wage state with a large agricultural sector that never achieved the same union strength as unions in manufacturing states, according to McKerley. The weakness of unions allowed the Iowa legislature to pass right-to-work laws in 1947, much earlier than other states. Right-to-work laws are laws that ban unions from requiring workers to join and pay union dues.

“There was a lot of fear about what right-to-work would mean,” McKerley said. “But [Iowa] workers were actually able to adapt to it and through organizing they were able to keep their memberships relatively stable through the fifties and the sixties.”

Unions related to the College

In 1969, Building and Grounds (B&G) employees at the College unionized, and when new-contract negotiations stalled a few months later, the new union members spent a week refusing to work.

Less than a year later, the B&G workers went on strike again, this time for ten weeks, leaving college administrators to do the B&G employees’ work. A picture in an August 1974 issue of The S&B depicts Waldo Walker, then executive vice president and dean of the College, mowing the Nollen House lawn.

Despite this burst of union activity in 1970s Grinnell, Logan Lee, economics, says that unions were largely in decline by then. Through a combination of globalization and deindustrialization, the American economy was changing, and it was a change unions weren’t prepared to deal with.

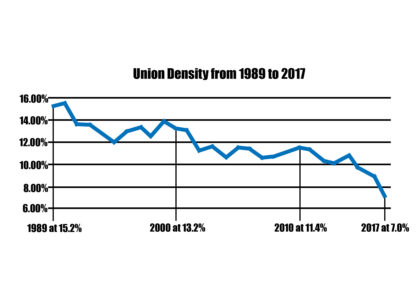

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that from 1989 to 2017 Iowa union membership fell from 182,000 to 104,000. The percentage of total workers who are members of a union fell from 15.2 percent to 7.0 percent.

In 2017, the Republican-led Iowa legislature passed new restrictions on collective bargaining rights for public-sector unions. The legislation bans non public-safety employees in public-sector unions from negotiating over health insurance and evaluation procedures, among other things. It also forces unions to hold a recertification vote every two to three years.

“I think pretty obviously all those laws are going to be bad for unions. They’re going to hurt public sector union membership, especially in the long term,” Lee said.

For some people, though, the original impetus behind labor unions’ creation may have dissipated, according to Lee. When labor unions originally formed they were pioneers in establishing the 40 hour workweek, a federal minimum wage and new safety standards. But many Americans now take those advancements for granted.

“People say, ‘Well, look. Unions have kind of served their purpose. A lot of the things that they used to fight for are now just federally mandated anyway,’” Lee said.

Conway shared that sentiment. He believes that while unions “served their purpose,” they “got out of control” and asked for too much from management.

“I think the unions have been their own demise,” he said.

Neither Lee nor Conway sees much hope for unions in the future. Even if legislation were passed to buttress unions in Iowa or elsewhere, Lee believes they would struggle to attract the kind of large-scale membership that would return them to an American political and social power.

McKerley, on the other hand, has a more optimistic view.

“There’s every reason that we could actually be at the beginning of a new era of union power that will take us in some direction that we cannot even imagine,” McKerley said. “Just like the workers in 1929 never could have imagined what the labor movement could become,” McKerley said.