By Kelly Page

pagekell@grinnell.edu

Passing through the mailroom, Grinnellians are presented with a counter covered with publications created by fellow students: art collections, books of literature and even sheet music. Any Grinnell student can submit their work to Press, a student organization devoted to publishing student work, and many mailroom publications have been one of the handful of works chosen each semester to publish and distribute to students for free.

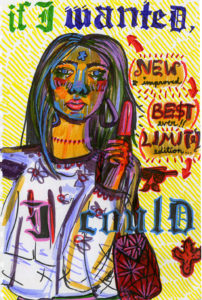

Amelia Darling ’20 published a book this semester called “You Have Your Whole Life Ahead of Me.” She describes it as “a collection of the stuff that came out of my head during the fall semester last year.” The book is a chronological look into Darling’s life as an artist and a writer, a collection of work from her journal and poems she wrote in a Grinnell class. Darling published the book as a way to find closure after trauma.

The book contains four sections, “Prelude,” “Entree,” “Learning” and “Forgiving,” each of which focuses on a distinct time in Darling’s life. Her journal entries, mostly in the form of drawings, are sometimes humorous, like a drawing with the caption, “Dragging my lifeless corpse to DHall at 12 PM after a night of debauchery,” but other entries are wrought with emotion, like a line drawing of a tree with eyes in the rain captioned, “Oh … It hurts.”

“It was kind of me reframing [trauma] to fit my narrative, so it gave me closure and gave me a start and an end,” Darling said of the book.

The inside covers of the book show a collage of men holding up fish on Tinder, just the tip of the iceberg of an ongoing project where Darling collects Tinder fish pictures.

“That’s been a project I’ve been working on for like five years. I have like 400 of them. I used to put them on Facebook but that just got to be too much,” she said.

Last year, Katie Ackerman ’18 published a book of photographs called “Sonder,” a made-up word from a YouTube series called “The Dictionary of Unknown Sorrows” which creates words for things that are not in the English language. The definition of “sonder,” printed within Ackerman’s book is, “the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.”

Like Darling, Ackerman’s book came from a very personal place.

“My grandmother really loved hands and she had passed away the semester before, and I’d taken some pictures of her hands and that’s sort of where I started, so I went around Copenhagen taking pictures of people’s hands, and when I came back I photographed people on campus and at home.”

Ackerman explores the idea that people’s personal stories can be told through their hands. The book shows her grandmother’s hands clasped on top of a quilt she made, two hands holding onto each other tenuously, a hand with purple nail polish holding a phone and many others.

Ackerman chose to put a quote from the American poet Sarah Kay in the book, which reads “Some people read palms to tell your future, but I read hands to tell your past. Each scar makes a story worth telling. Each callused palm, each cracked knuckle is a missed punch or years in a factory.” This is the philosophy that unifies “Sonder.”

Josie Sloyan ’18 also published a book last year, entitled “Ethics of Skin” after a Faulconer Gallery exhibit by Swedish artist Anders Krisár, which contained sculptures and paintings of young boys, some chopped in half or otherwise manipulated.

“I read a lot of literature about [the exhibit] because it was very interesting and spooky and what Krisár deals with is the space between connecting with a thing and penetrating it and the implicit violence in trying to access something,” Sloyan said.

Sloyan felt that the themes of the exhibit directly correlated with the themes in the short stories she had been writing for the past two years.

“The stories were things that I had written in the years before then and up until then, and it was lucky that I found something that I felt was thematic through the stories that I had written because I was trying to deal with the idea of violence and the rights of the writer to look at a thing and go into a thing and what kind of implicit violence was there,” she said.

The collection of eight short stories features sketches inspired by Krisár, which show simple figures in surreal representations. They represent much of the content of Sloyan’s writing, which often falls into the genre of magical realism. In the first story, “Josie Makes Excuses,” the speaker’s sister arrives for a visit as a ten-year-old vegan cat, “for security measures.” Another story, “Wings,” is narrated by someone who fell in love with a college student who has wings in her back. Sloyan’s stories also deal with darker topics, like “Incident (II)” which portrays a woman’s experience with sexual assault.

Sloyan sees Press as an important resource on campus for artists and writers.

“I think anybody who’s thinking about writing or thinking about their art should send their stuff to Press. Putting your stuff into the world like that as a collection and sort of the audacity of saying like ‘this is my book’ is a really important and scary first step for kids who want to be writers and artists,” she said.