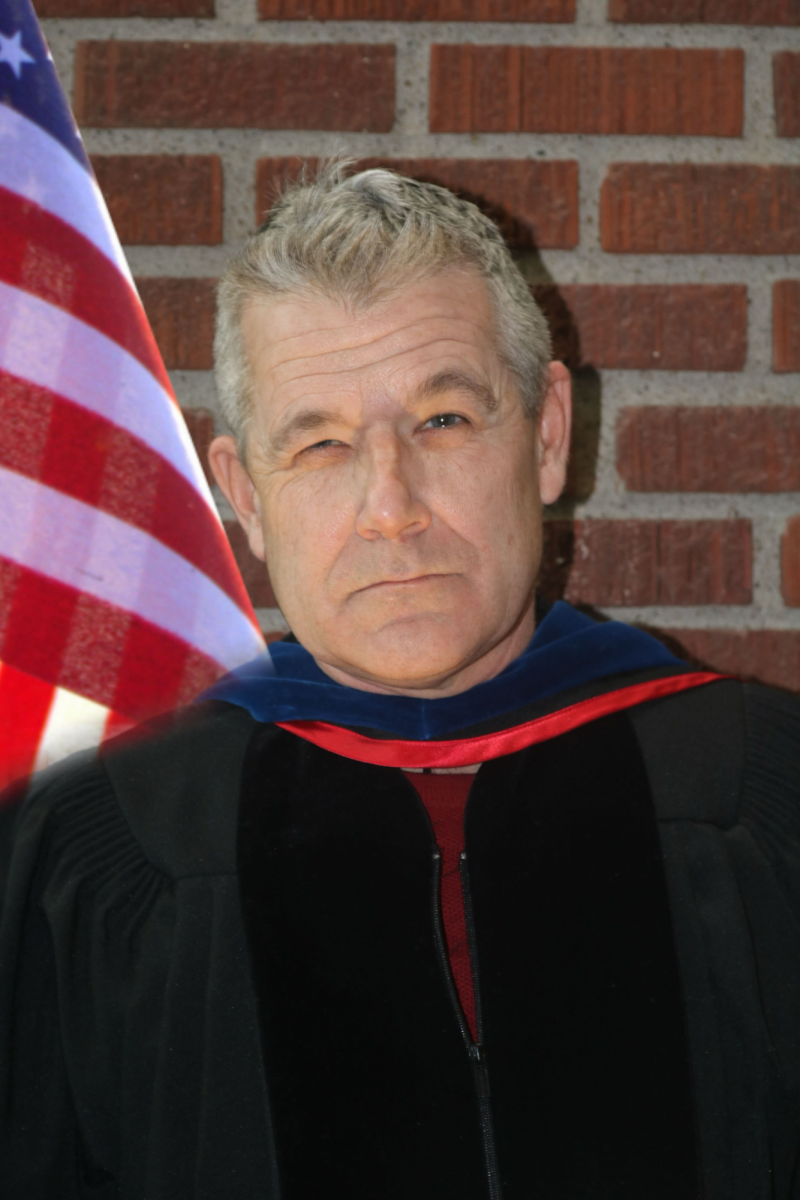

After months of campaigning, Carlos Cordeiro bested seven other candidates and emerged on Feb. 10 as the newly elected president of the United States Soccer Federation (USSF).

Cordeiro most recently served as the vice president of the USSF under former President Sunil Gulati, who announced he had no intention to run for re-election following the U.S. Men’s Soccer team’s humiliating defeat away to Trinidad and Tobago — a result which ended any hopes of World Cup qualification.

Although throughout the election cycle Cordeiro was portrayed as a continuation of the old regime by his opponents and detractors, in reality he possesses a unique skill set and comes from an unconventional background.

Born in India, Cordeiro immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 15 with his mother and siblings, eventually earning a scholarship to Harvard University, and, later, Harvard Business School. Following his time in Cambridge, Cordeiro worked in international finance for 30 years, including notable spells as an analyst helping South Africa’s post-apartheid government and as a partner at Goldman Sachs.

Experience in business and finance is likely a large part of Cordeiro’s draw, as the USSF has continually struggled to effectively invest in soccer at the grassroots and club level, especially in comparison to other world football powers, such as Germany, France, etc.

A key piece to improving the financial outlook of the program hinges on securing North America’s right to host the 2026 World Cup, a decision which could bring in large revenue shares as well as introduce American soccer fans to the world’s biggest clubs and players and vice versa.

Furthermore, greater revenue streams would also enable the federation to re-invest in youth soccer education programs throughout the country, which would hopefully make the game more accessible to socio-economically disadvantaged groups. For too long American soccer has been a game disproportionally played by white and middle-class children and families, and with club soccer team fees costing upwards of $5,000 a year, it is fair to the say the worlds game is leaving a whole lot of people behind.

A fundamental tenant of Cordeiro’s campaign was his commitment to equity and inclusion, and once elected he says he will appoint “a full-time, paid director of diversity and inclusion to promote equality across all programs for all athletes, regardless of gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, socio-economic background or disability.”

In addition to opening the game up to minority groups, the USSF also has an obligation to its female athletes, who, despite their prolific record in international play, have yet to receive equal treatment, recognition and pay when compared to their male counterparts.

These three issues — generating revenue, opening the game up to more people and leveling the playing field — will all be important for Cordeiro to address in his first few months in office. However, the biggest obstacle that he and his associates face is how to help grow soccer culture in America, as opposed to simply promoting soccer itself.

America is a relatively new presence in the greater football sphere, as four major hegemonic sports — basketball, baseball, American football and ice hockey — have long received the majority of interest and attention from our most impressionable and impassioned sports fans.

From an anthropological perspective, soccer in America is a reconfiguration, rather than a reconstruction, of identity. We market star players vastly differently, our stadiums are more sanitized and even the fact that we call the game “soccer” reveals important ways in which we have co-opted a global phenomenon to make it fit our local, idiosyncratic needs.

Further complicating soccer’s place is its vulnerable role as a supposed affront to the androcentric nature of violent, individualized sports like the NFL, MMA and UFC. Although stereotypes that portray soccer players as “soft” athletes have started to die down, it will always be hard for some fans to accept a game which, when played at its highest level, is about one team functioning as a smooth, single organism.

Despite these challenges, there is hope for the future. In recent decades hockey’s popularity has begun to dip and many youths are leaving football due to concussion research findings, two facts that, combined with a growing focus on America’s burgeoning immigrant population, have led to the rise of Major League Soccer (MLS). In addition to following local franchises, Americans have also turned out in droves to watch the World Cup, with television ratings indicating that the US — at least during the Cup cycle — consumes soccer at a clip comparable to its global contemporaries.

Thus, while the game readily dissipates to various corners of the country, it is having trouble permanently sticking in our cultural sports zeitgeist, a problematic notion that the new USSF president-elect hopefully has the tools to address.

In his role as an economic insider and a racial and cultural outsider, Carlos Cordeiro possesses the business acumen and the empathetic nature required to grow the American game in a way which is most accessible to the largest number of people.

Such an undertaking relies on a conception of American soccer as a global game practiced, played, and perfected in a local space — a notion which I believe Cordeiro understands better than most.