Several Pioneer football team members took a knee during the national anthem this past Saturday, as well as in games throughout this season and last. This past Sunday, Sept. 24, after U.S. President Trump’s comments that players who protest during the anthem should be fired, over 200 NFL players protested. The week before, just six NFL players knelt during the anthem to protest police brutality.

At each home sports contest, student event supervisors coordinate the playing of the national anthem, a task which includes putting up the flag and handling it properly according to the U.S. Flag Code, the legislative guide for displaying the American flag, according to Melissa Anderson, one of the student supervisors.

Over a year ago, NFL Quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem for the first time, which marked the beginning of this method of protest against racism and police brutality. Following this action, other players have begun to do the same.

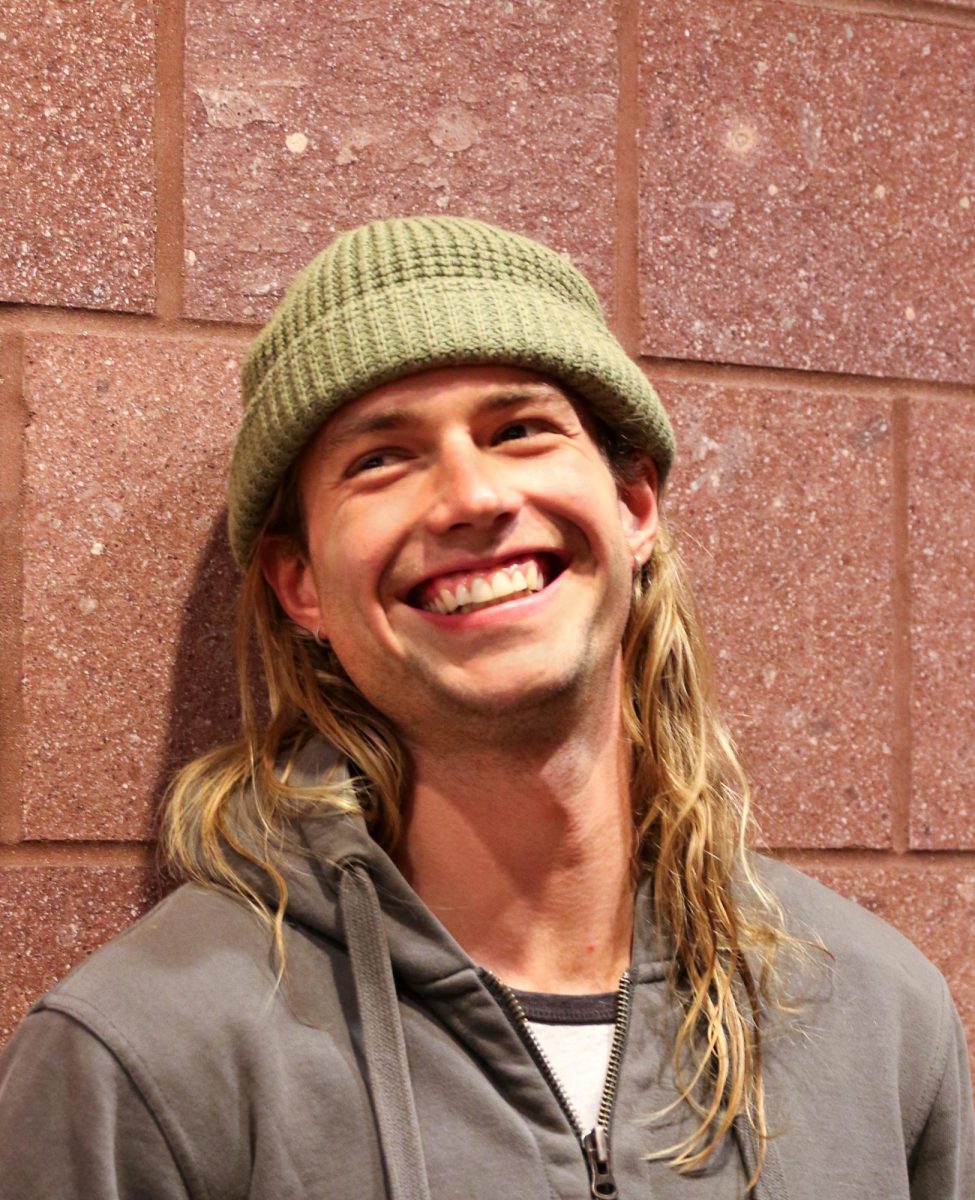

“[NFL protesters] are trying to get the awareness off the rich owners that always get … the fame and the fortune, while the Black people are just being their puppets and circus acts while they’re getting money. We’re waking up, so people are like, let me kneel and show that we’re not going to just keep being their puppets,” said Erik Henderson ’19, former member of the football team.

Closely following Kaepernick’s initial protest, some members of Grinnell’s football team began following his example, including Henderson.

“During the Civil War and the American Revolutionary War they had Black soldiers fight in the war, but once they returned, they weren’t allowed to get houses, they weren’t allowed to live in certain areas because of the fact they were still Black,” Henderson said. “Being a Black man in this country still, I am still held back even though we have been pushing for so long, so [for me, kneeling is] to bring awareness to this campus that I know this campus didn’t have.”

Last year on Military Appreciation Day, the football team had a dialogue with veterans about their choices to kneel. Some of the people they spoke to were receptive to their rationales, while others claimed the players making this choice were still disrespecting the country.

“My main point I was trying to get to was that I am still American,” Henderson said. “Even though I am kneeling, I live here, some of my uncles fought in wars. I have shown the same patriotism as you but I’m just trying to let you know that there is still [injustices] in this country … People have these views of athletes that they don’t care about social justice, so we’re acknowledging it here on this platform because we have a platform, we have people come to the stadiums and watch us play sports, so letting them know that we’re going to keep this conversation [going], even in athletics.”

One of Trump’s tweets on the national protests read, “If NFL fans refuse to go to games until players stop disrespecting our Flag & Country, you will see change take place fast. Fire or suspend!” His Twitter thread echoes criticisms that kneeling during the anthem disrespects the flag.

The huge increase in NFL players protesting was largely in response to Trump’s comments, with the rationale of standing in solidarity with those who do choose to protest regularly. The College and the athletic department support student-athletes’ rights to do the same.

College President Raynard Kington as well as Athletic Director Andy Hamilton and Assistant Athletic Director/Coordinator for Diversity & Inclusion and Student Programming Roepke support students’ decisions to protest during the national anthem, citing freedom of expression and supporting dialogue as important factors.

“I believe strongly that the athletes have the right to express their opinions as citizens and should do so without fear of reprisal,” Kington wrote in an email to The S&B. “Like so many other Americans, I continue to be disappointed and dismayed by the often inflammatory and divisive comments made by our President. I would expect more from any of the presidents of the more than 4,000 colleges and universities in this country, let alone from the nation’s president.”

“We are focused on the rationale and prompting of conversation and are welcome and receptive to dialogue,” Roepke wrote in an email to The S&B.

Hamilton also stressed that Grinnell, as an educational institution, has the opportunity to create conversations to address the concerns of our own athletes as well as national concerns.

“If someone wants to protest, do something different, they have the right. Communication about it is super important so that we can learn from it,” Hamilton said. “On our campus, we have a wonderful opportunity to discuss things and learn from each other and I don’t know that we have to come to a consensus, but a debate and deeper understanding of individual expression could be a byproduct about this.”

In the tutorial course that Hamilton teaches, “The Black Athlete: Changing 20th Century Society,” the class had a discussion about the national anthem, anthem protesting, Trump’s comments and protest in general, attempting to contextualize recent anthem protests.

“One [student] pulled up the original lyrics of the national anthem, and there’s a whole verse about slavery — I didn’t know that. Another student alluded to the protest that Rosa Parks made by sitting in the front of the bus, and that’s exactly what we’re trying to get out in this course — we’re looking at how we can connect historical events which happened in the 20th century to now.”