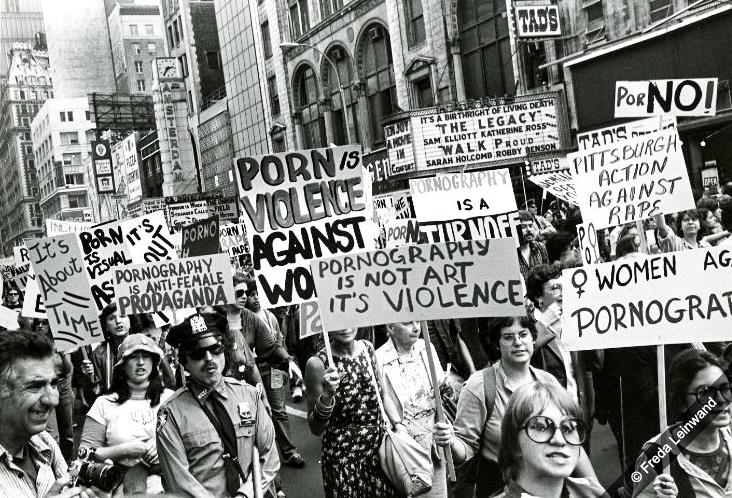

The sex wars of the 1980s were characterized by debates about the censorship of pornography as well as sex, sexuality and sexual practice. Today at 4 p.m., the two sections of the Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies (GWSS) senior capstone seminar “Bad Feminists/Bad Critics” will be arguing against each other, each section taking a position that the actors may or may not agree with, according to Professor Leah Allen, GWSS.

The seminar Bad Feminists/Bad Critics studies feminist figures and theorists who are no longer part of the mainstream feminist movement. One of these figures is Andrea Dworkin, who was a big player in the sex wars advocating for censorship of pornography.

“The gist of the semester is that it’s looking back at the way we tell the history of feminism and then specifically looking at those who are now left out,” Allen said. “So people who have been bad feminists and considered bad for that feminist cause, whatever that is. I say whatever that is because it’s a lot more nuanced than we think.”

This year is the second time the seminar will be reenacting this debate. The anti-sex, pro-censorship section will be arguing that pornography is violence against women because it affects their material lives, while the other pro-sex, anti-censorship side argues that censorship of pornography is a patriarchal attempt to censor women’s sexuality, according to Allen, as well as Julia Marquez-Uppman ’17, who will be arguing in favor of censorship of pornography.

“The basic facets of our argument are that porn causes material harm to women, [and] there’s a direct relationship between image and reality … This idea that in porn, not only the women who are actually having violence enacted against them, but also that porn causes those who watch it to reenact the behaviors they see and perpetuate the same violence,” Marquez-Uppman said. “Because porn is directly affecting women’s safety, yes, we’re talking about censorship, but the issue is not a censorship issue because porn is not free speech, it is violence against women.”

The anti-censorship argument, according to Allen and Marquez-Uppman, essentially won the sex wars, in the sense that it began the line of feminist critical theory that mainstream feminism engages in today. Many of the pro-censorship arguments that will be argued in this class are what the class has been reading: feminist theorists and critics whose writings are no longer representative of the current feminist movement.

“One of the biggest things is [that] no, it isn’t a free speech issue, [it’s] infringing on the first amendment by trying to censor anything. I think the most compelling argument of the anti-censorship side is that it reframes sex as a liberation thing, not as something that perpetuates violence but something that can be a space of freedom and self-discovery and pleasure, especially for women since women’s sexuality has been historically repressed and denied,” Marquez-Uppman said.

This year, there are enough students in the two sections to have a third role. Two students, including Merlin Matthews ’17, will be protesting the event from a position against both sides.

“We’re going to be protesting from a narco-feminist position of engaging in this debate and attempting to use the legal system to codify your positions is engaging too much with patriarchy and oppressive structures, so you’re all a bunch of sell-outs,” Matthews said.

The structure of the debate will include opening statements, rebuttals and closing statements. The two protesters will be using the time in between opening statements and rebuttals to make their points.

Allen noted that one valuable aspect of this debate for participants is the opportunity to do research on and take the point of view of a position they may not agree with. Although the anti-censorship position is most widely accepted, all three said that they see similar arguments among people today, although in different forms.

“In the 80s it was about dirty magazines … That was the context, but now we have all this new stuff, like we have revenge porn, that thing of teenagers videotaping their friends raping people. One of the biggest questions of the sex wars was the relationship between reality and representation and how much an impact an image has on life and I feel like the way we interact with images is very different now than it was then,” Marquez-Uppman said.