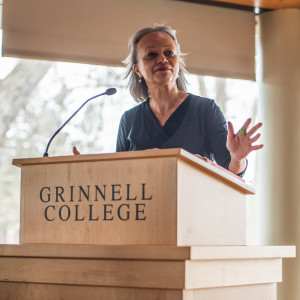

This past Monday, Jan. 19, Grinnell College sponsored a teach-in to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Patricia Williams, the James L. Dohr Professor of Law at Columbia University, delivered a teach-in, entitled “Hoping Against Hopelessness: An Anatomy of Short Lives.”

A recipient of the 2000 MacArthur Fellowship, Williams was a pioneer of critical race theory in the 1980s. At Columbia, she teaches classes in feminist legal theory, justice and human rights. She also writes a monthly column for The Nation entitled, “Diary of a Mad Law Professor.”

“It was a great opportunity to see one of the best in foundational black women and critical race theory come to Grinnell … That type of woman is … a model of a successful black feminist,” said Cristal Coleman ’15.

The Monday teach-in started with a lecture at 10:30 a.m., followed by a break for lunch and then a discussion section at 1 p.m. Poonam Arora, Chief Diversity Officer, Associate Dean for Diversity and Inclusion and one of the organizers of the event, said, “We decided that we would use [Martin Luther King Jr. Day] and students would be told to come back over the weekend so they would be here. So we carved out this day for [the teach-in], which is otherwise very difficult to do.”

The teach-in did not focus on Martin Luther King Jr.’s life, but instead used the theme of “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution,” the title of the talk Martin Luther King Jr. delivered at Grinnell in 1967.

“[The teach-in] wasn’t so much a celebration of MLK Jr., but rather a celebration of his ideals and his philosophies and how they can be applied today in our global or immediate context,” said Armando Perez ’17.

JRC 101, where the event was held, was filled over capacity for the 10:30 a.m. lecture.

“It was super exciting just to see so many people in JRC 101 … [At the convocations] there are never that many people there, and this was absolutely packed,” said Lucy Chechik ’18.

Williams’ lecture centered on the different experiences of black and white Americans, focusing on policing practices, disparities in media coverage and the “two-tiered justice system” for blacks and whites. She described how the New York City Police Department more heavily polices predominately black neighborhoods, arresting young black men for infractions that most would not even consider a crime, such as riding a bike on the sidewalk. These differences in policing practices, she said, lead blacks to “experience the world through a disparate lens.”

“She drew on technological aspects … scientific aspects, and just by mentioning phenotypes, pulled together so many different languages to talk about being black in America,” Coleman said.

Williams also spoke on the importance of “reaching across conceptual boundaries” and the influence increasing globalization has had on “racial dynamics from Ferguson to France and back.”

Before breaking for lunch, Williams ended her lecture by emphasizing the importance of “learning to face the world with more resilience, history, education and kindness.”

The second part of the talk, a discussion, resumed at 1 p.m. The purpose of this unconventional format, according to Arora, was to “slow down the pace of the delivery of ideas,” and to facilitate discussion on how to address these issues.

During the discussion, Williams answered six questions taken from the audience regarding how to ensure activism on campus is effective, the presence of the two-tiered justice system on college campuses and Williams’ own identity as a black woman.

“A well-prepared, very finished, very impressive talk that simply comes and wows everybody is not what we need. We need people to interact and we need an institutional thinking-through,” Arora said. “I worked with Professor Williams to … open up conversations.”

According to Arora, the intention of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion is to continue the conversation that began in Williams’ teach-in.

“It is very early to say what shape it will take, but the way we planned it, we want it to be a marathon … The audience’s presence, participation and standing ovation … are symptoms that the institution and the society need to do something,” she said.

Continuing the conversation, however, may not be enough, Perez added.

“We can only talk about something for so long and pat ourselves on the back [because] we discussed it … and then it’s tricky, because what is it that we can do?”

Photo by John Brady.