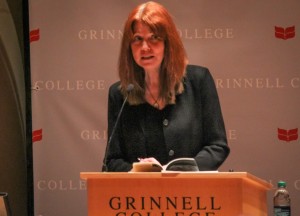

Julie Kane gave a roundtable discussion and reading in the JRC this Thursday, Nov. 14, as part of the Writers@Grinnell program. Dungy is a poet, editor and scholar, known for her books “Rhythm & Booze” and “Jazz Funeral.” She is also a professor of English at Northwestern State University of Louisiana. The S&B’s Kelly Pyzik sat down with Kane after her reading on Thursday.

What is your relationship with form?

I do have free verse poems in my new manuscript. I have been going back to it, part of the time at least, but I still feel like when I start working on a form that I haven’t done a lot of work in before, it almost makes new subjects or moods possible that I haven’t tackled before. There are just certain subjects and tones that go with forms. I haven’t really exhausted them all yet. … People often think that form is going to restrict you and reduce the possibilities of the poem, but for me it’s very paradoxical, it seems to be more liberating, it seems to set my mind freer to come up with things that are fresh and original or surprising.

Your poetry tells a lot of stories but it also does a lot with language, where do you see yourself working on the plot-intensive vs. language-focused spectrum?

I find it interesting that you said stories because I wouldn’t consider myself a narrative poet but it’s true, there are some little vignettes. In terms of language, if you take away the meanings of the words I’m using, it’s almost like the poem is a little abstract musical composition, just the sounds and rhythms and tones of it. It’s like a kind of music. Sometimes I don’t know what the word is going to be, but I know it’s going to be some kind of heavy syllable. It has to have a certain shape to it, or something. It’s almost like composing, but the words mean something, too, you’re playing with both things at once.

Your poetry has a strong sense of rhythm, what is your creative process for that?

I’ve gotten some criticism from the strict metrical poets or critics. They’ll say that I’m not uniformly iambic, or whatever, but often I’m working with more accentual rhythms. I might have four strong beats in a line, not an iambic line, and I can hear that rhythm in my head and I can hear the beats but somebody else might say it’s not scanning … I don’t know where it comes from, but even when I do free verse I can hear the beginnings of [a rhythm] in my head. Even when you have a metrical grid, the poem itself is playing against that, it’s never going to match up exactly. I’ve said before that it’s like there’s a rhythm section and then you have a singer singing over the rhythm section, doing little prolonging notes or trills and things. You’re observing that beat but you’re sometimes a little bit ahead of it or behind it. A lot of it is not really conscious, but my ear knows when it’s not right.

You’re the head of the spoken word poetry team at your university, but you don’t really write spoken word. What is your relationship with that?

I would love to [write spoken word], but I just look at the poets that I admire who are working in spoken word and my own students and it’s kind of like, if you’re not very good at throwing a softball, are you going to go out for the team? I don’t even know if I could do what they do, but I admire it tremendously and I really think that when people look back on this age in poetry, spoken word, rap [and] hip hop [are] going to be an important component of it.

The voice in your poetry is often very blunt and straightforward, and you don’t usually come across like that when speaking with an audience, where does that come from?

I guess that’s because in poetry it’s always a persona. Martha Vertreace once said that her poetry begins in autobiography but then she has to turn the volume up, and that’s kind of what I do—that persona in some of those poems is much wilder than I am these days, maybe not in my youth … In a poem you’re going to make the poem what it needs to be, you’re not worrying about how you’re presenting yourself. You can’t worry about whether anyone is going to like the ‘you’ figure or about trying to be nice.

During the round table, you talked about the significant benefit of using bodies and vocality in reading and writing and how it has sort of fallen out of style. Do you want to bring that back, or how do you think it can be brought back?

I think it’s happening now with spoken word poetry, definitely, and rap and hip hop, and with the internet, with YouTube videos of poets reading. In the past, you would have to just read a poem on the page, but now you can actually hear it voiced. New formalist poets, too, who are writing in rhyme and meter are writing to be sounded out, not just those ideas going to your rational mind. I do think there has been an upsurge in poetry meant for the ears and not just the eyes in recent years.