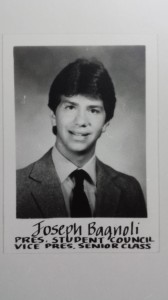

As part of a monthly column, Remy Ferber ’14 reaches out to members of the administration to write about their college experiences and more. This week features Joe Bagnoli, Vice President for Enrollment and Dean of Admissions & Financial Aid, who graduate from Berea College in 1988 with a major in business and a minor in music.

What was your favorite course?

Sociology of Everyday Life with Professor John Crowden was my favorite class. It was one of those courses that forced students to confront biases and stereotypes and to examine how media serves to introduce and perpetuate them. I especially recall the important insights on androgyny that radically transformed my views on constructs of masculinity and femininity in society. To this day, that class influences my views on parenting, media-related exploitation of young women in service to conspicuous consumption, and the incomplete perspectives of movements, organizations and churches dominated by patriarchal structures of authority.

What was your best spontaneous decision?

When studying abroad in France through course-embedded travel, our professor told us we would have a free day in Paris after we had already seen many of the hallmark sights of the city. I quietly organized a group of students to flee the city on the TGV [Train à Grande Vitesse] so we could see the infamous South of France, an otherwise unscheduled component of the one-month cultural tour of France. I got in big trouble for leaving Paris, but it was worth it!

What separated Berea from other colleges?

The student body at Berea is strictly comprised of those from families who lack the financial resources to pay tuition. As far as I know, Berea is the only college in the U.S. that would deny admission to an otherwise qualified applicant whose family did not have demonstrated financial need. Berea provides every student with a full-tuition scholarship and requires them all to work throughout their four years in college. So most students at Berea were the first in their families to attend college and, in many ways, the kind of people Malcolm Gladwell would eventually refer to as, “outliers.” Our enrollment, persistence and eventual successes were unexpected or at least not predicted, based upon the absence of social, cultural, human and financial capital invested in us up to that point in our lives. But the Berea students I encountered were amazingly talented, determined and resilient. They beat the odds, so to speak, by devoting themselves to the daily tasks of hard work, in and out of the classroom. Most seemed to keep their heads down, perhaps feeling like impostors or hoping that no one would notice that people like them “didn’t really belong in college” or were not expected to be successful. Most were wildly successful, however. My first roommate is a medical doctor, my best friend became a school system superintendent and another in my closest circle of friends is a chief financial officer for a public regional university.

What was the biggest issue on your college campus?

The biggest issues for us seemed less about what was occurring in the world beyond campus or things affecting everyone on campus and more about finding our way individually and collectively through a disorienting series of academic, social and cultural exercises that sometimes seemed contrived to apprehend and banish from cognition every last trace of conventional wisdom about life that had been nurtured in us since birth. Everything was challenged—personal biases, religious convictions, political ideologies, assumptions related to race and ethnicity, immaturity and even self-deprecating behaviors. Engagement with the wider world around us was often limited to encounters with the diverse range of enrolled students at Berea. Televisions, telephones and the time to read a newspaper were luxuries. There was no such thing as the Internet. Neither were most of our families very well-connected to the world. Other students, professors and supervisors at work unwittingly deconstructed and redesigned our lives around the organizing themes of inclusive Christianity, interracial education, the dignity of all work and appreciation for the beauty found in things like art, music and theatre. These were our “big issues,” and as I think of the whole experience now, I realize how fortunate we were to have the luxury of escaping the noisiness in the rest of the world to redefine ourselves over those four years.

What has changed the most about you since college?

This is sad to admit, but I’m far less idealistic than I was in college. The thing I love about the college years is that for a brief window in time, it seems like anything is possible.

Through a variety of personal and professional challenges in life, I have come to believe that not all things are possible. Even with hard work, stamina and intelligence, it isn’t always possible to affect the world as we would like.

What would you do if you went to Grinnell today?

I would definitely be in the Grinnell Singers and the G-Tones. I would be sampling courses in the social sciences and diving deeply into those with sociological and anthropological roots.

What do you still want to know about the Grinnell student experience?

One of the most unexpected things I encountered since arriving at Grinnell in 2012 is the happiness level of students here—everyone I know seems to love being a student at Grinnell. I’d like to know what explains that. Recently, a woman who was an admission counselor at Grinnell before doing similar work at other national liberal arts colleges told me that Grinnell students are the happiest ones she’s ever encountered. Why is that?

![When [bagnolij] was in college...](https://thesandb.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Bagnoli-Contributed-20131027_233503-2-BW-1024x579.jpg)