Sustainability efforts at Grinnell have been bolstered by the creation of four new paid student positions on the College’s Sustainability Committee: energy coordinator, transportation coordinator, food coordinator, and communication coordinator.

The creation of the positions is a shift from previous endeavors to tackle sustainability challenges at the College, which are often spearheaded by unpaid volunteers involved with environmental groups.

These positions, supervised by Environmental and Safety Coordinator Chris Bair, are new this semester as a result of a student-led push toward institutional support for sustainability. Sharene Gould Dulabaum ’22 serves as the committee’s energy coordinator, Will Chapin ’23 is the transportation coordinator and Lucia Cheng ’23 works as communication coordinator. The food coordinator position has yet to be filled and was only recently posted. Bair also supervises recycling coordinator Ally Rogers ’21 and compost coordinator Peter Barth ’22, whose positions existed before this semester.

Each student’s role falls within one of seven steps in the College’s Sustainability Plan, which was created by the Sustainability Committee in 2013. Students in these positions will lead a subcommittee organizing efforts to their respective sustainability focus. Funds for the positions are sourced from the Sustainability Committee, which is funded entirely by gifts.

After a student-led fossil fuel divestment campaign failed to sway the Board of Trustees, Student Environmental Committee and Student Government Association’s Green Fund have worked toward progress in other areas of the College’s environmental impact.

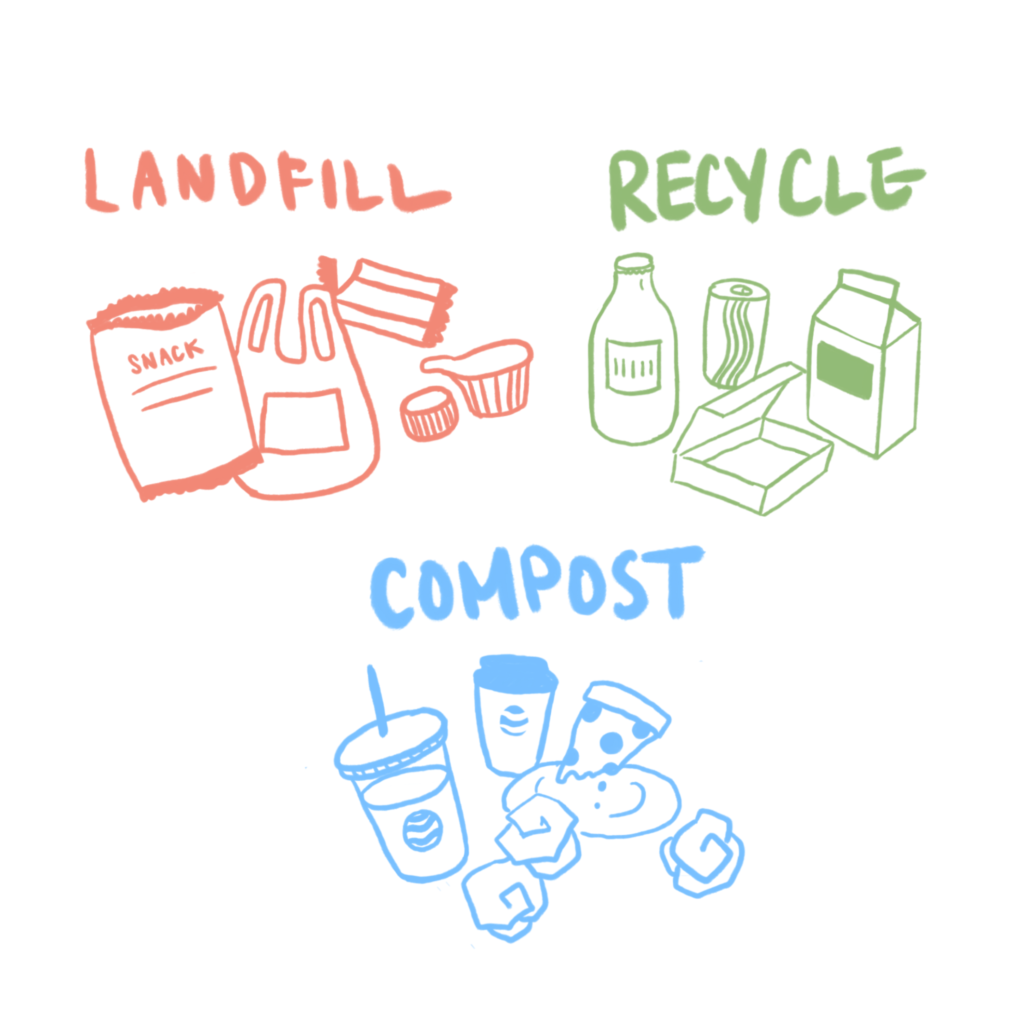

Last year, industrial composting was implemented on campus, resulting in Green Fund providing compost bins to students in dorm rooms and dorm kitchens as well as Dining Services’ shift to compostable disposable products. Still, the path to sustainability has not been entirely smooth. Compost and recycling bins across campus and particularly in the Spencer Grill are often contaminated by non-recyclable or non-compostable products. Additionally, waste which can be recycled or composted frequently ends up in the trash.

The confusion over where waste belongs may also be complicated by the city of Grinnell’s recent policy changes. As a nationwide result of China’s 2018 decision to restrict the waste from the United States accepted for processing, Grinnell no longer provides single-stream recycling and can only collect plastics one and two. Glass and other plastics consequently either end up in the trash or contaminate the recycling bins.

“I just think a lot of people were just not trained to think, like, ‘Where’s my waste going?’ … When people think about where to throw away their waste, they don’t think about, ‘Am I putting in the right place?’” said Gould Dulabaum, who also serves as co-leader of Student Environmental Committee. “Signage is also not consistent. … I understand why there’s so much confusion because it’s not easy. … There should be signs, at least in some places, that tell you what can and can not be recycled, and same with composting,” she said.

Industrial compost bins, located in the north, east and south loggias and outside the Harris center, are also often contaminated. “Sometimes there’s tin cans or aluminum cans or glass bottles. … I once found a whole empty case of San Pellegrino,” said Barth, who brings each bin to the compost dumpster behind the Joe Rosenfield Center each week. “Every time there’s at least one bin that has a wrong thing in it.”

Composting has also yet to expand to academic buildings. Last semester, a trash audit conducted on the Humanities Social Sciences Center revealed that the majority of waste coming out of the building is made up of paper towels, which are compostable. Aside from the contamination, the increase in recycling and compost bins on campus has ultimately been positive for sustainability at Grinnell.

“I still think it’s been an example of a success story, especially when it’s started by students, which is really great.” said Bair.

Students’ position at the center of efforts to make the College more sustainable, while successful, has also been a source of frustration for student groups who want to see sustainability prioritized through the creation of a formal sustainability office.

“There’s only so much we can do because a lot of [student sustainability work] is unpaid. … The reason we have compost is because of student initiatives, it’s not because of administration,” said Gould Dulabaum. “With everyone working together, we should be able to have like an informal sustainability office in a sense. … I think student environmental groups on campus have also been working on obtaining a physical space where we can organize, … that’s another way that we can create a sustainability office without the College even saying there is one.”