Almost a year ago, the parent of one of Kevin Hosbond’s students filed a complaint regarding a book taught in his ninth-grade English class. Just two short months later, Republican Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds signed Senate File 496 (SF 496) into law, a sweeping education bill placing restrictions on instruction material and requirements for a clearer process for parents to make formal challenges.

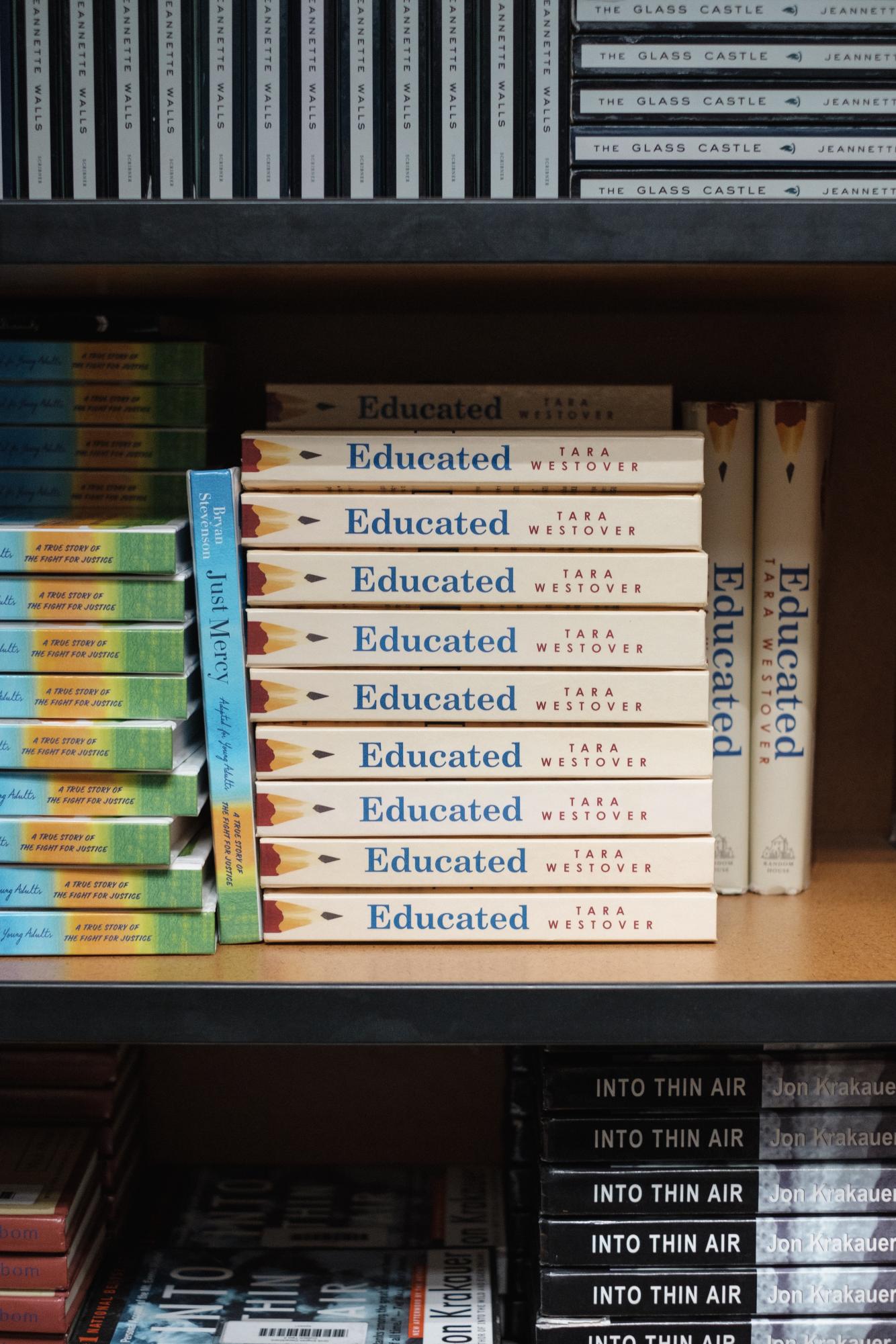

“I was ready to stop being a teacher,” Hosbond said of the attempt to remove the book “The Glass Castle” from his curriculum at Grinnell-Newburg High School (GHS).

“It seems like Iowa just keeps giving us more parameters, confines, to work within. And I can’t see any of those being beneficial to students,” he added.

Reynolds disagrees. In a written statement from Nov. 28, 2023, she wrote, “Protecting children from pornography and sexually explicit content shouldn’t be controversial.”

Since the passing of SF 496 in May 2023, the Grinnell-Newburg school district has been preparing to adhere to the law, removing books that may violate the law from libraries and creating a public catalog of all material kept in libraries.

But SF 496, a 17-page-long document, packs quite the punch — legislators etched several restrictions over education into Iowa state law, namely banning the use of materials seen as not “age-appropriate.” For example, materials depicting a sex act, as defined by state law, are considered not age-appropriate under SF 496.

The bill also put forth a requirement for a more streamlined, transparent process for parents wishing to challenge material in a school’s curriculum. Under the law, school districts are required to detail the process of challenging instructional material or a school board’s decision and to display this explanation clearly on a school website.

Penalties for school districts not adhering to SF 496’s guidelines were slotted to start going into effect on Jan. 1, 2024. Those determined by a board meeting to be knowingly violating the law can face disciplinary action.

But before the new year deadline, two lawsuits filed in Nov. 2023 blocked the state of Iowa from enforcing the law based on two major parts – the restriction of instruction materials depicting sex acts and the restriction of instruction concerning gender identity and sexual orientation at the K-6 level.

Despite the lawsuits’ rulings, teachers in the district report a climate where educator self-censorship is becoming increasingly prevalent due to fear of backlash.

“Every time I talk, I just feel like I’m on eggshells,” Hosbond said. “I’m often qualifying everything with ‘In this location, in this time period, certain individuals,’ so that it doesn’t come across like I’m saying bad things about America or that everybody’s racist.”

“It feels as though the intent is to make us self-censor,” Jennie Flinspach, another English teacher at GHS, said of legislation like SF 496.

Flinspach said she has sometimes felt “gaslit” by legislators.

“They sit and tell me when they have no training in education, in English, in anything, they know better than I do,” she said, speaking to her two master’s degrees. “And when all I want — I will swear on a stack of whatever you want that all I truly want is to help the kids learn.”

Hosbond said before the start of this academic school year, the English teachers at GHS went through the school’s English closet — where GHS keeps hundreds of titles of books — to try to redesign the English 11th-grade curriculum.

“We went through a lot of these titles that easily would fit into an English-level curriculum,” he said. “But almost every book had ‘Oh, there’s this one sentence where the couple does something, it’s mentioned that some activity happens that’s sexual.’”

According to Hosbond, one of the other English teachers said, “I’m not touching that. I just don’t want to risk it.” The teacher Hosbond referred to declined to interview, citing her lack of union protections in the first two years of her employment at GHS.

Chelsey Kolpin, media specialist at Grinnell Middle School and GHS, wrote in an email to The S&B that around 10 to 15 books at the high school and around 5 at the middle school were removed. She added that all books were stored in her library office. Kolpin declined to offer a list of the books removed at this time.

When determining when a book violated SF 496, Kolpin wrote she received guidance from the Iowa Association of School Librarians and the Central Rivers Area Education Agency. She also said she reviewed books she knew to be questionable and decided whether to keep them in the libraries based on the state’s definition of a sex act.

Before the major blockages on SF 496, school district leaders said they received little to no guidance over how to follow the law in the months winding down to the Jan. 1 deadline. With the law’s language, which has been termed broad and vague by opponents, several teachers and school district members said they were left confused about where to start implementing provisions of SF 496.

“As a school board member, all we’re asking for is literally some guidance of, okay, show us what is bad, show us what is good, so we can move on,” Chris Starrett, president of the Grinnell-Newburg Board of Education, said.

The parent who filed “The Glass Castle” complaint last year is Starrett’s wife. But Starrett said he remains steadfast in his obligation to serve the district first.

“It was my wife that had to put the name because I had to stay neutral,” he said of the formal complaint.

“Regardless of what my viewpoints are, my constituents are the ones that put me in that position, and I’m going to follow through with what they believe,” added Starrett. “I have to represent the school district, not our views, not my own views.”

Brianna Schwenk Maschman, district curriculum and diversity, equity and inclusion director, said that in the face of the “information vacuum” the district faced on how to adhere to SF 496, Grinnell-Newburg turned to resources outside of the Department of Education for guidance.

“As a result of the passage of the bill, all the districts in Iowa really then were holding their breath and waiting for instructions, clarity, guidance from the Department of Education,” Schwenk Maschman said. “And that guidance really never came.”

Schwenk Maschman said that in the months since SF 496 passed, the district made the process of filing a request to review instructional materials more accessible for parents and removed the ability for students to participate on reconsideration committees, as SF 496 requires. GHS students served on the reconsideration committee for “The Glass Castle” last April and May, which ultimately ruled to keep the book in the curriculum with alterations.

She also said the district made a catalog of library materials available to the public but chose to not catalog individual teacher libraries in classrooms.

Parts of SF 496 still remain unaffected, including a requirement to report to parents any student wishing to go by a different name or pronouns contrary to a school’s official registration records. The same section requires educators to not knowingly give false or misleading information to a student’s parent or guardian on their gender identity. Some opponents see the provision as an attack on trans students, forcibly “outing” them.

“It’s like they only want a certain type of kid graduating, turning 18 and voting,” Hosbond said.

Flinspach said that in a poetry unit for one of her classes with a course theme of identity, only “A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be” by trans poet Ethan Smith has ever been contested by parents — even among 15 other poems discussing topics like race and mental health.

But Flinspach added that trans students told her they felt supported by her inclusion of the poem.

“Last year, when there were more trans kids than usual in a class, several of them told me how it was refreshing and how it was supportive to have their identity reflected just like everybody else’s was,” she said.

Flinspach, who helps lead GHS’ Gender and Sexualities Alliance, and Hosbond both said they fear what the state of Iowa will look like in the future as an increasing amount of transgender legislation is debated.

Hosbond said his family moved to Grinnell from Fairfield seven years ago shortly after a controversy erupted over which bathroom transgender students should use at Fairfield schools. At the time, he thought Grinnell would be “the right kind of place.”

Yet, “a different voice has risen,” Hosbond said, referring to the local political climate. “And as the laws continue to attack those kinds of kids, yeah, we worry what are we going to do for our kids. Are they going to be bullied, or are they going to be bullied from afar by legislation?”

“I’m indecisive about the future of my career,” Hosbond added. “And it really is because of legislation.”

Starrett said he was not familiar with the details of how the school district as a whole was complying with the requirement for teachers to report name and pronoun discrepancies to parents.

On instructional material, Kevin Seney, principal of GHS, and Steven Barber, interim superintendent for the district, both said challenges and complaints remain few and non-serious.

The S&B reached out to several educators at Grinnell Middle School for comment. None were immediately available to comment.

Update: In a follow-up email sent to The S&B after this article was published, Kolpin said the books removed from GHS and Grinnell-Newburg Middle School libraries have now been returned to the shelves.

Chelsey Kolpin • Mar 17, 2024 at 3:14 pm

I’d appreciate you adding that the removed books in the GHS library were returned to shelves due to the stay on the law with the impending lawsuits. This information was given in our email exchanges.