History Takeover: The first time graduation was cancelled, 1970

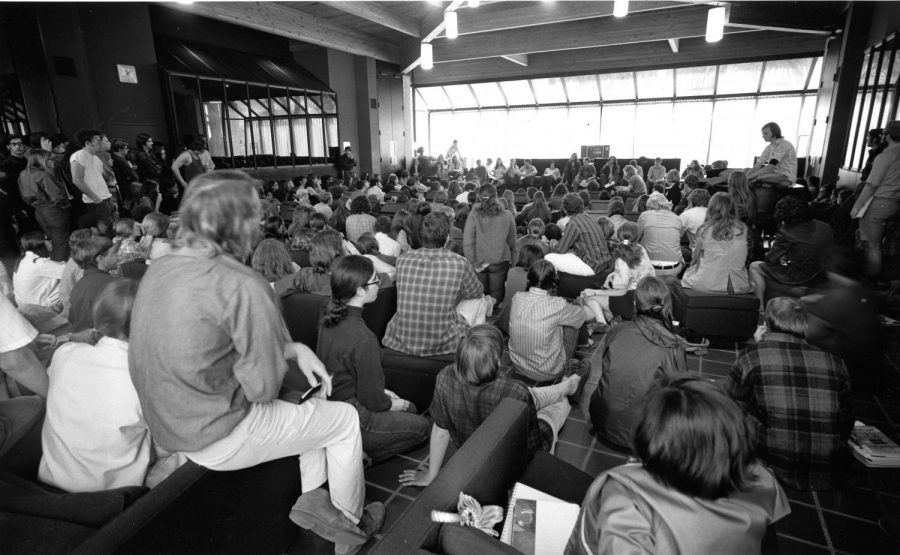

Taken by George T. Henry, contributed by The Grinnell college library archives

Students gather in the Forum for a senate meeting about the four students killed at Kent State University in May 1970.

February 20, 2023

On the path between the Bucksbaum Center for the Arts and Burling Library, a sweeping row of low-slung trees surrounds a hefty boulder. The rock bears a plaque that begins,

“The Peace Grove

A gift of the Class of 1970

June 1, 1991”

Compared to similar monuments across campus that commemorate individuals or enshrine the legacy of graduating classes, the Peace Grove’s plaque seems out of place. The Class of 1970 had left Grinnell 21 years before the Grove’s dedication in 1991. The vague inscription raises more questions than answers. The Peace Rock celebrates — or perhaps mourns — a crucial moment in Grinnell’s history.Though 1968 is often remembered as a year of high societal tensions, 1970 might have represented the peak of unrest on American college campuses. As the Smithsonian Magazine recounts, many colleges had long opposed the Vietnam War. Especially at more liberal schools, students and faculty alike felt the war to be an unjustified, immoral endeavor. So, when President Nixon announced that the U.S. was launching “attacks … to clean out major enemy sanctuaries in Cambodia,” thus expanding the scope of operations in Southeast Asia, students revolted.

At Kent State University in Ohio, students reacted with particular force. After an unknown arsonist burned down the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) building on campus, the National Guard arrived. On May 4, the National Guard opened fire on a crowd of students, killing four and wounding nine others.

Grinnell students responded to the shooting with rapid fury. Just a few days prior, on May 1, The S&B had made no mention of current events, even noting a “famine of news on campus.” The next edition, on May 8, ran the headline “Grinnell Closes Doors In Protest”.

Between the three articles that ran in the S&B that month, as well as a May 2020 piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education, a portrait emerges of students emboldened and enraged. The Chronicle wrote, “students knew that activism could create change on campus.” The Kent State shooting seemed to prove to students that the United States was sliding into authoritarianism and continuing to attend classes would signal complacency.

First, on May 5, students went to occupy the ROTC building on campus. The Grinnell Police Department, hoping to avoid violence, offered little resistance. Tensions escalated with “some rock throwing and a few smashed windows” on campus, according to Howard Hagen `70.

On May 8, the College faculty voted to cancel classes, final exams and commencement. As a way of explanation, College President Glenn Legett wrote, “the College [could not] continue to carry on its normal and traditional functions in the next two weeks” given the polarization on campus.

Heated debate and name-calling occurred throughout the process. In a speech, Andy Loewi, then president of the Student Government Association, claimed that Grinnell was “beginning to witness the same kind of irrational repression that occurred in Nazi Germany.” On the other hand, an unsigned letter in The S&B decried the protest’s leaders as “budding young fascists.”

In an interview with The S&B, Hagen said that he understood the College’s decision to close its doors. He cited an atmosphere of “paranoia,” yet he, and most of his peers, felt disappointed.

“The class never got over it,” Hagen said. Likewise, his father “never forgave the College for not having a graduation.” Tensions dissipated and graduates moved on, but the sense of theft — that the ceremonial reward for four years of work had been stolen — never disappeared.

Nora Hoover expressed similar disappointment in an email, admitting that “it was disappointing.” However, she also stressed that commencement is symbolic. “The important thing,” she wrote, “is that I obtained the degree. Not having a graduation ceremony did not prevent me from following my path or being successful … Not having a degree would have.”

In some ways, the story ended as soon as it began. Grinnell’s campus emptied, students grew apart, separated by physical distance and the communication technology of the time. Classes resumed in the fall with little disruption.

In other ways, though, the impact has never disappeared. As Hagen put it, the Class of 1970 “can never go back.” To this day, Grinnell’s website claims that “We’re known for our strong tradition of social responsibility and our commitment to justice for everyone” — a statement forever brought into question by the events of May 1970.

The Peace Grove may seem like nothing more than one of many dedications around campus, used for the occasional picnic or outdoor study session. Yet it captures a turbulent moment in history and symbolizes the weight of an unfulfilled promise.